A very stylish vintage watch this time, a 1940’s Zenith Sporto.

(Click pictures to enlarge)

First introduced in the mid 1940’s, the Sporto was one of Zenith’s longest enduring model ranges. In direct competition with Omega’s Seamaster dress watches which were first introduced around 1947/48, the Sporto range really hit its stride during the 1950’s with classically designed models featuring both black and ivory dials.

Although manually wound Sporto models continued throughout the entire production cycle, automatic movements found their way into the range during the 1960’s. Though the design aesthetic remained exactly the same (the watches were just thicker to accommodate the additional winding mechanism), the automatic models were branded ‘AutoSport’ on the dial, making it easy to tell them apart.

Production continued well into the 1970’s, with later models being fitted with Zenith’s excellent 28,800 bph, cal. 25xx range of movements.

It is thought that the Sporto / AutoSport models were retired in favour of the Defy range some time around the mid 1970’s (an example here), though the model ranges were produced simultaneously for a short period.

The watch in this post is one of the earliest Sporto models and was produced in 1949. It has a very elegant look with lumed arabic numerals, dauphine hands and the oversized seconds subdial being a standout feature. Though the patination on the dial and hands won’t be for everyone, personally I don’t mind it at all, the dial and hands are all original and have aged evenly – the watch is 75 years old after all.

Turning the watch over, the caseback has an interesting inscription on the snap-back case: “Tir Cantonal Vaudois, Moudon, 1.50” which refers to a shooting festival held in the Swiss canton of Vaud in January 1950. One of Switzerland’s 26 cantons, Vaud has held an annual shooting festival in one of its municipalities since 1825, the event in 1950 taking place in Moudon. Whether this watch was a prize given to a successful participant, or was just produced to commemorate the event, I can’t say.

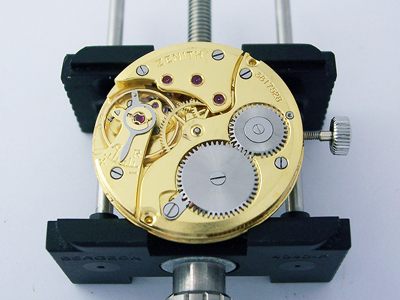

With the caseback removed, the movement is revealed, a Zenith cal. 126-6. It is protected by a clear acrylic cover, which was only included on the early models, to better shield the movement from dust and moisture.

The calibre 126 movement is manually wound with a beat rate of 18,000 bph, typical for the period, and was in production from 1947 until 1956. Produced in four variants, the 126 and 126-5 had a subdial and centre second respectively, and the calibres 126-6 and 126-5-6 had the same configurations, but with the addition of incabloc shock protection. The serial number on the movement here dates this watch to late 1949, which ties in nicely with the caseback engraving.

Arriving in non-running condition, the problem was immediately obvious from the near-zero winding resistance – a broken mainspring.

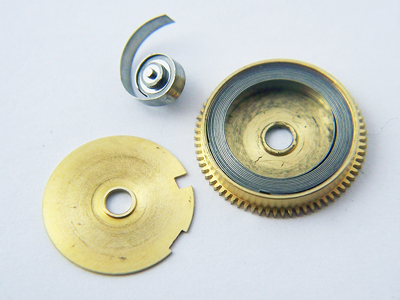

As is often the case with watches from this period, the type of mainspring used has long been superceded and finding replacements can be difficult. In this case the calibre uses a ‘double brace and hole’ (DB&H) mainspring which has ‘T’ section at the hook end, along with a hole in the centre which slots over a hook on the inside of the barrel.

If you look closely at the picture of the mainspring barrel above, you will see one raised section of the T-End protruding above the spring on the outer edge. The barrel cover has a slot cut into it (the shallowest of the two slots, the deeper slot is used to gain entry to the barrel when closed), which along with a hole in the bottom of the barrel, must be aligned with the T-End so that it presses against it when wound.

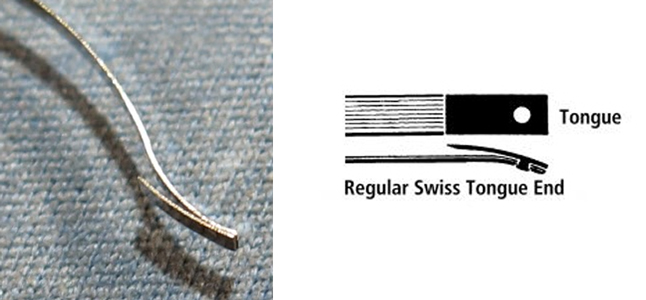

It’s a very secure system, but has effectively been deemed overkill with the passage of time. Most modern mainsprings for manually wound watches have the much simpler Swiss Tongue End, which hooks into a groove on the inside of the barrel.

I was pleased to find that a suitable DB&H mainspring was still available to order, which solved the main issue with the movement, the only additional thing required was polishing for a few of the screw heads which were showing signs of tarnish.

With the movement back up and running, the case was disassembled and cleaned and the crystal polished. However, during re-assembly, I found that the acrylic crystal had shrunk, as they have a tendency to do after several decades, so that too needed to be replaced to finish the job.

Rich.

** Many thanks to Ken Hodson for letting me feature his watch on the blog. **