Long-term readers will know that I’m a fan of Seiko Bell-Matic alarm watches and while I’ve covered almost every aspect of them on the blog already, this Diashock model is a rarity and well worth a closer look.

(Click pictures to enlarge)

The Bell-Matic first appeared in 1966 and was initially produced just for the Japanese domestic market. Featured in the early catalogues alongside the now legendary 62MAS diver and the 5717A single pusher chronograph, the earliest Bell-Matics have subtle differences to the models produced later for the wider market and are rarely seen, especially in the west – the owner of this watch had to ‘duke it out’ in the early hours on a Japanese auction site to secure this one.

At first sight there is little to distinguish the watch from any early 4006-7000 which were all fitted with 27 jewel movements, striped dauphine hands and a simple red triangle for the alarm bezel pointer. The Diashock branding and the ‘linen’ pattern dial are a couple of key differences, the former referring to Seiko’s proprietary anti-shock system for the balance wheel.

First introduced in 1956 and fitted to the majority of vintage Seiko calibres, the Diashock branding featured prominently on many Seiko watch dials throughout the late 1950’s and 60’s, from the simple models right through to the high-end Grand Seiko’s.

Later in the production cycle, the same 4006-7000 model was made with both 17 and 27 jewel calibres, in three dial colours (black, white and silver) and had baton hands with luminous filling. The alarm bezel pointer was also changed to a luminous white triangle on a red background.

However, it’s the case on the earliest model where the majority of the differences lie. Turning the watch over, the caseback is completely different compared to a later Bell-Matic. The obvious difference is the central dolphin motif and lack of the traditional ‘horseshoe’ design seen on many vintage Seikos. In addition to the brand name, model number and ‘Water Proof’ markings, the ‘S S’ at the bottom denotes that the whole case is made from stainless steel. There were no gold plated versions of the early watches.

The serial number is clearly visible in the centre, the first two characters ‘6N’ dating the watch to November 1966 and ‘53978’ is the production number. At the time of writing there is only one known Bell-Matic with an earlier serial number, so if you have a Bell-Matic with a lower serial number than this, please let me know.

Pictured side-by-side with a regular Bell-Matic caseback, you can see that the shape is also different as the early caseback has a higher ‘dome’ for the automatic winding rotor.

The early caseback also has the model number on the inside and the cut-outs for the case opener have a raised section in the centre. Why? I don’t know, I’ve never seen this before on any Seiko.

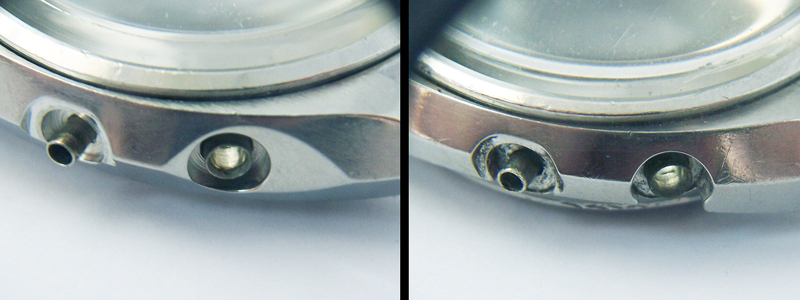

The main case too has an obvious difference, a ‘notch’ for the alarm pusher which was also phased out later in the production cycle. Here are the two case types together.

On the inside, as denoted on the dial, the watch has the more refined 27 jewel version of the 4006A calibre – for any interested readers, I wrote this post highlighting the differences between the 17 and 27 jewel 4006A calibres.

Scruffy but complete, the movement looked to be in decent condition. A hint of wear on the outer edges of the movement plates. most likely from a previously worn rotor bearing, but overall, pretty good. The long tail of the alarm sounding spring was clearly visible and a good indicator that the movement is original to the watch as the long springs are only found in the earliest calibres.

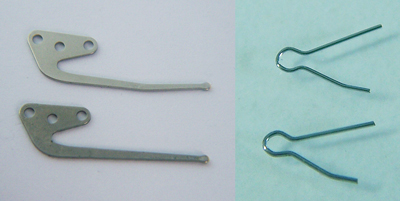

Here is a picture of the sounding spring with one from a later 4006A calibre for comparison. When the alarm is triggered, the longer spring results in a lower tone than the shorter spring.

It’s been 10 years since I last wrote about a Bell-Matic on the blog, but hardly a week goes by that I don’t service/restore one. So, even though I thought I’d seen pretty much everything by now, there were still a couple of surprises inside this watch. The first being the dial. On most Bell-Matics the dial has either a separate plastic spacer or a metal spacer attached to the back of the dial into which the dial feet are mounted – see an example here.

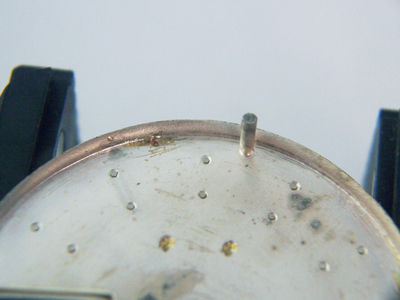

On this watch, the edge of the dial itself was rolled down to form a thin lip which acts as the spacer and the dial feet are elongated to compensate for that, which is something I hadn’t encountered before.

Inside the movement there were also a couple of really subtle changes (this is turning into a post for the hard-core Bell-Matic enthusiasts, apologies to everyone else if you’re nodding off!) The date corrector spring has a bend in the early calibre, phased out in later iterations and the alarm bolt yoke spring was slightly thinner than the one used in later calibres. Other than that, the calibres were identical.

I do get asked quite often how accurate the alarms are on vintage mechanical alarm watches and the truth is… not very! The Seiko service manual for the Bell-Matic states that the alarm should ring within +/- 5 minutes of the bezel pointer and that is pretty typical of most vintage mechanical alarm watches in my experience, which rely purely on friction rather than the luxury of an electronic trigger. Personally, I aim to set them up so that they always ring before the minute hand hits the trigger point, as there’s not much point in having an alarm that rings late.

Disassembling the movement uncovered a few issues commonly seen on Bell-Matics, the alarm bezel clamps were both broken, the alarm unlocking wheel was worn and date ring numerals had some damage. Being only transfer printed, these numerals are very easily damaged, any hint of oil or moisture can cause the transfer to float off the base and a replacement is then the only option.

With the damaged parts replaced, the rest of the movement was in pretty good shape and needed no more than a routine service. The case was cleaned, crystal polished and new caseback and alarm pusher gaskets fitted to complete the job. You’ll see on close inspection that the stripes on the hands do show some signs of damage from previous removal and fitting, but it was decided to leave them as-is to preserve the originality.

Rich.

** Many thanks to Keith Donnelly for letting me feature his watch on the blog. **