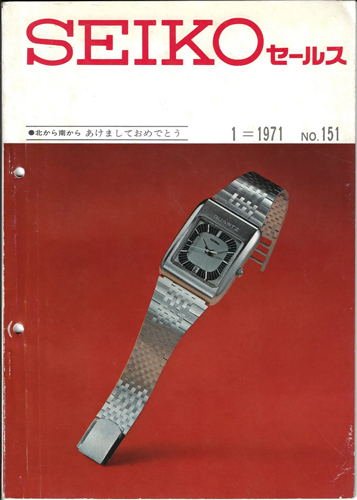

I’ve been looking at a few vintage quartz watches over the last few months, this Seiko 3923-5010 V.F.A. being one example, and a real eye-catcher.

(Click pictures to enlarge)

Several watch manufacturers had been developing quartz calibres throughout the 1960’s, but it was Seiko that were the first to market with the Astron 35SQ in December 1969. Despite costing ¥450,000, the same price as a small family car, they still found buyers (100 in the first month) and the model signalled the start of the quartz revolution.

Since 1959, Seiko had been split into two wholly owned subsiduaries, Suwa Seikosha and Daini Seikosha, in which no development information, movement design, or parts were shared, effectively making them rival companies within the Seiko brand.

Whilst the story of the Suwa Seikosha produced Astron 35SQ is well known in watch circles, what isn’t so well known is that Daini Seikosha were developing their own quartz calibre at the same time, the 36SQ, which was released in 1970. Doubling the internal clock speed of the 35SQ (from 8192Hz to 16384Hz) and with an increased accuracy of 0.1s/day (3s/month), the 36SQ claimed to better the 35SQ in all aspects.

However, despite featuring in Seiko catalogues, it’s not clear whether the 36SQ was ever commercially released as no examples have been found in the wild, though there is an example displayed in the Seiko Museum in Tokyo.

Following the release of the Astron, Suwa further developed the 35SQ, making technical and design improvements, resulting in their 38 series of quartz calibres. Daini also continued to improve the 36SQ, producing two calibres, the 3922A and the 3923A, the only difference between the two being the inclusion of a day display for the 3923A.

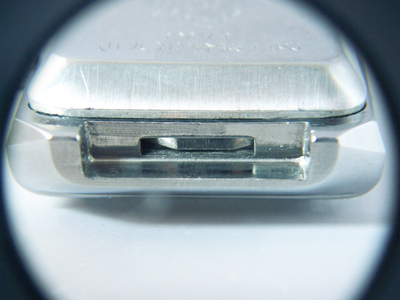

Now on to the subject of this post, the Seiko 3923-5010, which is unusual in many respects, the first being the case design. What isn’t apparent from a head-on shot is the profile of the case which has to be seen side-on to appreciate fully.

The faceted crystal is wedge shaped in profile with bevelled edges and has the white ‘Quartz’ moniker transfer printed on the underside. The case is a mix of polished, brushed, curved and angular surfaces, and the caseback is curved to follow the shape of the wrist. In terms of dimensions, it’s 32.5 mm wide (excl. crown), 41 mm from lug-to-lug and 16 mm thick, so it wears well and occupies the middle ground in terms of wrist presence.

Turning the watch over, from the serial number it can be deduced that this watch was made in August 1973 and the inscription reads; “20th Award Remembrance – Okochi Memorial Foundation, 1974, Sankyu Incorporated”

Founded in 1918, Sankyu Incorporated are a major Japanese logistics company and since 1954, the Okochi Memorial Foundation have been awarding individuals, groups of individuals, or companies prizes to recognize their contributions to Japan’s industrial technology. Each year, one Okochi Memorial Production Prize and five Okochi Memorial Technology Prizes are awarded, the 20th Production Prize being awarded to Sankyu Incorporated in 1974. (Many thanks to James Darsley for the translation.)

Much like the 7016-5001 chronograph from the Daini stable, the case is opened by depressing two recessed clips between the lugs, after which the case top can be lifted away from the crystal and lower case.

The crystal and gasket can then be removed and the stem is released through a hole on the right hand side of the dial, after which the movement can then be lifted from the case. In the bottom of the case is a blue plastic shield which insulates the movement from the metal lower case. There is a fair bit of paint loss around the edge of the dial on this watch, but thankfully that is all covered by the crystal gasket when the watch is fully assembled. The flashing LED is visible in the top right hand corner of the dial, but more on that later…

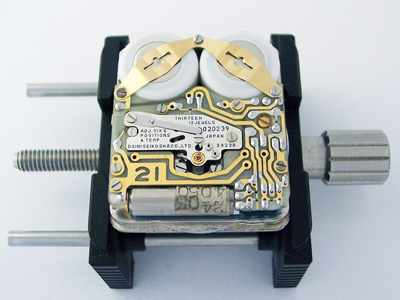

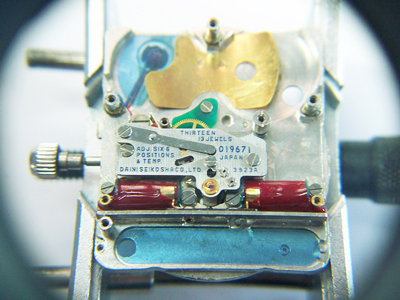

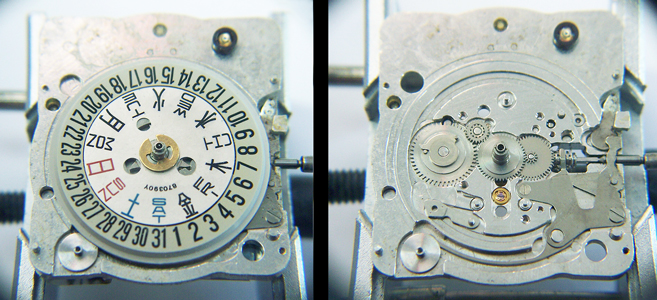

… and so to the cal. 3923A movement, which is really quite something.

Produced for just 4 years, 1972-1976, the 39 series calibres were the flagship of Daini’s quartz production. Hand soldered and adjusted to six positions and temperature, they were accurate to +/-10 seconds per month, hence the ‘Very Fine Adjustment’ (V.F.A.) branding on the dial. By today’s standards that doesn’t sound very accurate, but in 1972, 0.3 seconds/day was excellent timekeeping for a quartz calibre.

The top third of the movement is dominated by two large SR44SW batteries working in parallel to provide 3 volts of power, double the amount of required by most quartz calibres. The batteries are housed in two white plastic shields to insulate them from the rest of the movement.

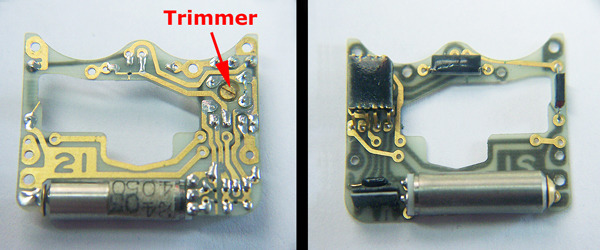

The printed circuit board contains the quartz crystal (housed in the silver tube) and the CMOS controller chip which is fitted with a trimmer for fine tuning the accuracy. It’s interesting to note that the quartz crystal in this calibre was precisely cut to ensure optimum performance between 84 and 88 degrees, the typical temperature of the skin, ensuring that the watch was at its most accurate when worn.

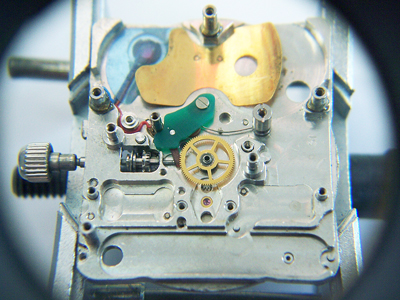

With the batteries and circuit board removed, it still doesn’t feel like we’ve made significant in-roads to the heart of the calibre. You can see the red and blue wires extending up to the back of the LED on the top left and under the quartz capsule is another blue plastic sheet to insulate it from the mainplate.

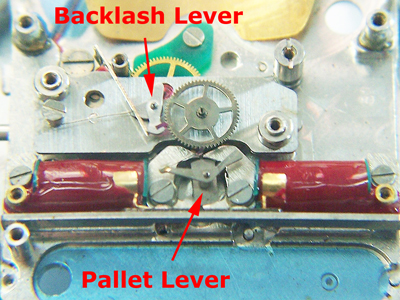

The next part to be removed is the train bridge, underneath which is a pallet lever mechanism, very unusual for a quartz calibre. Rather than a stepper motor which rotates in one direction, the 3923A has a bi-polar stator arrangement (the two red parts), reversing the polarity alternately moves the pallet lever back and forth, advancing the wheel train once per second. The second jewelled lever is present to control any backlash, resulting in a very solid second hand action.

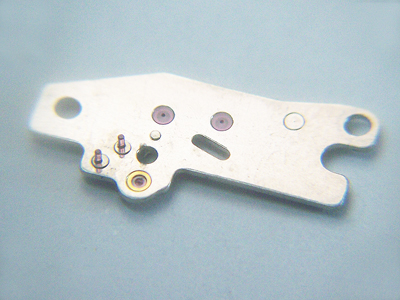

The amount of pallet lever travel can be adjusted using the two eccentric screws in the train bridge, which are fitted with jewelled banking pins on the underside. I assume these are jewelled to avoid any chance of magnetism and to reduce wear over time.

We’re getting down through the levels now, the final two sections being the wheel train and hacking mechanism, which arrests the centre wheel when the stem is pulled out. You can also now see the two wires for the LED which are attached to two of the mainplate posts, completing a circuit when the PCB is in place.

On the calendar side, things aren’t quite so complicated, thankfully. The calendar wheels are printed to display the day and date vertically at the six position and anyone familiar with vintage Seiko will probably note the similarity of many of the parts with the 7xxx series calibres from the same period.

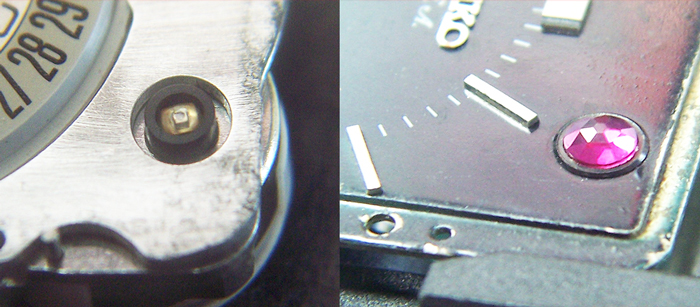

The last thing to highlight is of course the LED which is located in the top right corner of the dial. The LED filament is mounted inside a plastic ring on the calendar side of the movement and the dial is fitted with a faceted jewel which covers the LED housing and projects its light in all directions.

The LED flashes once every second and aside from being cool, its real purpose is to give an indication of the level of battery power. When the batteries are new, the light is bright and it fades gradually until the light extinguishes completely, at which point you know that a battery change is imminent. Battery life is quoted to be somewhere around a year if everything is in good working order, which isn’t very long in modern terms and isn’t all that convenient really given that significant disassembly is required to change them.

With the movement fully disassembled, only around 60% of the parts could be safely cleaned in the cleaning machine, so the rest were carefully cleaned by hand.

I haven’t really worked on quartz watches since my days at watchmaking school and the feelings of ‘will this thing work when I re-assemble it?’ re-surfaced. As parts for these watches are non-existent and fault finding would have been a headache, I was pleased to see it jump into life when new batteries were installed.

With the movement up and running, the case was cleaned and the watch rebuilt to complete an interesting project.

To finish this rather lengthy post (congratulations if you’ve made it this far!), I’ll just say that these watches were produced in a variety of colours during their short production run. Here is a picture from a Japanese catalogue showing the full range.

They were produced mainly for the Japanese market and not very many found their way west, so you may struggle to find one in the usual places, but happy hunting if this watch appeals to you.

Rich.

Thank You for this detailed post ! In meantime I got two of these – one badly damaged by battery leak, one nearly perfect and running. Except the LED flashing. I‘ll change the batteries to find out. I’m collecting early electrics and Quartz watches – would be great to stay in touch ! Instagram watches1815